SAMPLE THE BOOK

Chapter 1

The Fisherman

He snapped the fish’s neck quickly and efficiently, as he had done so many times before. He quickly cut its throat and bled it over the side so the flesh would not become tainted. With a backhand flip of the wrist, the fish spun into the old wooden box in the hold of the boat.

“Fuck…” he said quietly to himself… “salmon.”

He brought the net over the transom with a slow steady motion, pausing briefly to remove a fish now and then. Each fish was dispatched with an economy of movement. Occasionally the silence was broken by the phrase “Fucking salmon” or just “Fuck”.

The net coiled on itself in the bottom of the boat, shiny with water.

A large gummy shark came struggling over the transom, tail thrashing in a froth of water. He pinned it to the deck with his fist and wrestled it from the net. A sharp blow to the head with the old ebony ruler and it was subdued. Quickly bled over the side of the boat, it was tossed into the box.

His mood slightly improved, at least the shark was worth some money, unlike the salmon which he virtually gave away, such was the lack of demand.

His watch, salty and scratched with its faded web strap, told him it was still early. Time to set the net again he thought.

The old Yanmar diesel clattered into life and he motored slowly to another spot where he usually had some luck. The early morning was still dark so he could not navigate by his normal marks, land-based features which he triangulated by eye. The small depth sounder under the stern deck told him which way to go. There were some advantages to technology, despite his attempts to remain indifferent to it in all its manifestations, especially depth sounders and navigation aids. He refused to use a GPS to navigate. He knew where he was going and used the marks on the horizon all around him as his guides. He needed nothing else. When it was dark, he used the compass and the feel of the boat as it moved through the water. Occasionally he would use his grandfather’s old sounding line to check the depth. Handmade from whipcord, waxed with a 10-pound lead weight on the end. It had markers woven into the whipcord every yard, so one could count when the line was hauled in. Every 10 feet the marker was red, so you could count the depth more easily. He did not use it often, only when he lost his bearings, which was not often. He knew the Bay, its shoals and channels like the back of his hand.

It was still dark when he arrived at his mark. He cut the motor and set the net quietly using the momentum of the boat. The last float over the side, he poured some coffee from the old metal vacuum flask. Dented and scratched from years of use. The coffee was barely warm but still good. A cold cooked sausage and a cold boiled potato left over from last night’s dinner made for a welcome break. The mark was over a small reef which he had fished for years. It was quite productive but too small for larger boats to bother with. He said a silent prayer to the Fish God, asking for a snapper or two, perhaps a half dozen whiting. He did not think that was an unreasonable request having regard to the shit catches lately.

Salmon and mullet were reasonably prolific and able to be caught for most of the year. Snapper and whiting were much less so and confined to spring and summer. The top reaches of the Bay did not fish as well as the bottom reaches. However, he seldom made the long run to the bottom of the Bay, as he had done so many times in his youth.

He finished his meal and drank the now cold coffee from the battered steel flask. The sun suddenly broke the horizon in a blaze of orange as he watched silently. Soon he set to work cleaning and scaling the fish in the box. Guts were flicked over the side to the ravenous gulls, now floating eagerly behind him. “Choke on that you bastards,” he said happily.

He sluiced the deck clean with seawater from an old metal bucket tied to an even older rope. The bilge pump coughed and started automatically. It spat out bilge from the stern, oily and pink at the same time. The rainbow slick drifting away slowly, the surface of the water like glass in the early morning.

He washed his hands with the cold seawater, drying them on the front of his trousers, stiff with salt. The boat had drifted silently some way from the net as he had intended. Now he coaxed the old diesel into life. With a cough and clatter, and a billow of black smoke, it started. Time for a service he thought to himself, maybe not just yet though. He would take the boat out of the water soon and get Yanni to service the old diesel.

Yanni, the old Greek mechanic, had a small workshop in the next street. He assumed that Yanni was short for some Greek name, Yiannou or similar. Most people called him Yanni or Wrench which he seemed to prefer. Yanni did not charge a lot for a service. However, each time he took the boat to Yanni, there were mutterings about things to be replaced. He did not have the money for a new engine. Yanni knew that and was adept at finding old parts or adapting others to fit. As long as he was putting about in the top of the Bay, he was content to have the motor running on one cylinder rather than two. If need be, he would put up the sail and drift home as his father and grandfather had done. The motor was added by his father in the late 1950s when sailing became too slow for modern times.

He cut the motor and drifted over to the net. The old boat hook slid under the fish float and he began to haul in the net. A steady hand over hand pull, while coiling it in the bottom of the boat, brought it in quietly. By now the sun was well over the horizon and the water glinted and sparkled as it fell from the net. The promise of a new day and a full net were as shiny as the water. His mood lifted as it always did when he was bringing in the net. Even after all the years, some optimism if not enjoyment at the simple pleasures of fishing remained. A small snapper broke the surface, entangled in the net. Flapping and splashing, he carefully untangled it. Full of wounded pride and embarrassment the fish was shiny and sleek, its long dorsal fin a row of nasty spikes. The pink hue on its flanks gave it the colloquial name, pinkie. It was a good sign and he was almost happy. Where small fish were found, usually larger ones were not far away. He knew it was undersized just by looking at it, but he checked anyway. The old plastic measuring ruler secured onto the transom by his grandfather was long gone. These days he used the notches cut into the gunwale by his father. The short one for whiting, the middle one for salmon and mullet and the long one for snapper. Not even legal as a mullet, he tossed it well back away from the gulls so it would have a chance. “Fuck you”, he said to the gulls who glared at him with malevolent eyes. “Catch your own”, he said. The gulls replied with a chorus of indignant squawks. Another haul of the net brought in two more undersize pinkies and one just legal. He returned the undersize fish over the side, making sure the gulls were avoided. The legal-sized fish was quickly despatched and flicked into the box. He was becoming almost cheerful although the net was only halfway in. A good-sized gurnard followed, stocky and spikey but beautiful orange with the classic blue and yellow butterfly pectoral fins. One of the prettiest fish in the sea and one of the best eating. Sadly, the market for gurnard was limited. It was so unusual looking that the housewives from Brighton could not bring themselves to buy one. Hopefully, he would sell it to the local restaurants or maybe the pub. A few more barely legal pinkies and three good size gurnards followed. All went into the box together with a slurry of ice and saltwater. The remainder of the catch consisted of yellow-eye mullet and a few salmon. All nice sized fish, fat and sleek. He cursed each one as they were tossed into the fish box. “Fucking mullet …”, “Fucking salmon …”, “… Bastard …”. He was even-handed with his derision and equally vehement regardless of either species. His grandfather had fished these same waters and made a living from barracouta or couta as they were known. An oily fish with beautiful aquamarine marbled flanks, they were caught in great numbers. In his grandfather’s day they were the staple of working-class people. Grilled fresh or smoked, they were a wholesome fish which were cheap. Salmon and mullet were also very popular. However, those days were long gone. The boat he still used had been bought by his grandfather expressly to catch barracouta. Couta boats were seaworthy and fast but could carry good loads of fish in the hold. His father had made a living catching couta as well but by the time he had retired the market for couta had almost gone. White fleshed fish like snapper and kingfish had become the market leaders. Oily fish like couta, mullet and salmon were very hard to sell. After his father retired, the market for oily fish kept declining. But the fishing for snapper was good until the 1970s when the scallop boats began to overfish the Bay. The box dredges ripped up the seabed like a plough destroying the reefs which fed the snapper. The snapper fled the Bay in protest and the fishery all but collapsed. Times were very hard for the Bay fishermen, especially in the top of the Bay. He took to fishing the bottom of the Bay, making the long run from Port Melbourne each night. For a while he was able to make ends meet but the bottom of the Bay soon became less prolific. He switched to kingfish which, by that time, had become a desirable restaurant fish. The best and most reliable fishing ground for kingfish was the Rip. Not many professionals fished the Rip, it being widely considered to be too dangerous and unpredictable. He was one of the few who fished the Rip routinely and it was good fishing. The fishing was hard and dangerous, but the catches were usually good. He came to know the Rip and the run down from the Bay from Port Melbourne like the back of his hand, often making the run while half asleep, especially on the way home. However, the Rip was not always reliable and there were times when he used his nautical skills for purposes other than fishing. Syd the Squid would call him from time to time and offer him a job, either ‘body’ or ‘bag’. Each was a term referring to illicit pick-ups from foreign vessels usually in the Rip. A ‘body’ job was a shivering seaman in the forecastle of the boat. A ‘bag’ job was a pick-up of a package thrown over the stern of a container boat on a dark night in the Rip. He never looked inside. Both were good money, but he did not like the work at all. After a few years, the scallop dredges were banned in the Bay and the fishing picked up. He preferred fishing to the body or bag trade. It was safer and made him feel less uneasy. yd was very disappointed with him when he went back to fishing and still offered him the odd job. Sometimes he said yes; but each time he said it was the last. “You said that last time,” Syd would say. “Get fucked,” he would reply.

A dolphin surfaced and started nosing around the net. He quite liked dolphins, unlike seals they had a friendly disposition. At least he liked to think so. He had liked dolphins since he was a child. Whenever he saw them, he would feed them with a fish or two. His father did not like them but tolerated his affection for the animals, if only to try and create a bond with the boy. In truth, his father did not like dolphins and, like most fishermen, saw them as a competitor, if not a pest.

As time went on the Fisherman became more affectionate towards the dolphins. He saw them as a token of goodwill and a bringer of fish. If dolphins were about then he knew the fish would follow. The truth was probably quite different. Dolphins were intelligent and knew where to find a free feed. In truth, all the fish were declining so a dolphin had to make do with a Fisherman’s net or simple goodwill. At all events, he tossed the dolphin a mackerel. It was gone in a gulp. The dolphin chittered and was gone with barely a swirl of water. So much for a partnership between man and dolphin.

Some may think the chittering of a dolphin was a thank you. He would have liked to think so. However, he knew that was dolphin for “thanks for the fish, … loser”, as they ate your fish and swam away. But he just liked to look at them. If they came to the boat, he fed them so that they would stay, at least for a while. They were company on the long days spent in the boat. He set a course for home and rigged a few silver blade lures out on long lines. With a little luck he would pick up a kingfish or two. A kingfish would help as they brought quite good money at the markets or restaurants these days.

He turned to the remaining salmon and other fish in the boxes. They were very bloody fish which must be bled and gutted immediately, before the flesh deteriorated. He worked quietly and efficiently, a backhand throw of guts over the side the only punctuation to his work. The gulls squawked and fought for the guts which twisted in the wake. The only good use for salmon is burley, he thought to himself. Nonetheless, he treated the fish respectfully as he would any animal which he had killed. He slid the fish into a slurry of ice and seawater in order to keep them as fresh as possible.

The diesel clacked noisily in the background, the fumes filling the cockpit.

In the past, a few boxes of salmon or mullet would make a modest profit for the trip. These days it would not break even. Once again, he would make a loss on the trip as diesel had become so expensive. He could not recall when he had made a good profit on a trip. Indeed, he could barely remember the good days, they were so long ago.

He was relieved when the motor started, belching black smoke. The sun was well above the horizon and he turned for home. The tiller was set with an old rope tied to the stern at one end. The run home was not long, but it might produce a big fish if he was lucky. He threw a handline with a metal blade lure flashing at the end. You cannot catch a fish if there is no gear in the water, he could hear his father say. Indeed, his grandfather had said the same thing. Unfortunately, it did not seem to make much difference these days. The lure bounced and flashed in the water just like it was supposed to do. The fish, if they were there, did not do what they were supposed to do. He cleaned and scaled the fish, tossing the guts to the gulls screeching and diving in the wake.

He took each fish from the box and placed it on the board. It was scaled quickly and efficiently. The first cut was from the vent to the throat. The entrails were removed with a second flick of the knife. The next cut was from behind the gill plate and pectoral fins, from neck to throat. One cut. One cut only. The third cut was along the backbone down to the tail. The last cut was from the neck to the tail, through the rib bones. The final step was to remove the bones and belly. Once again, one cut. A simplicity of motion.

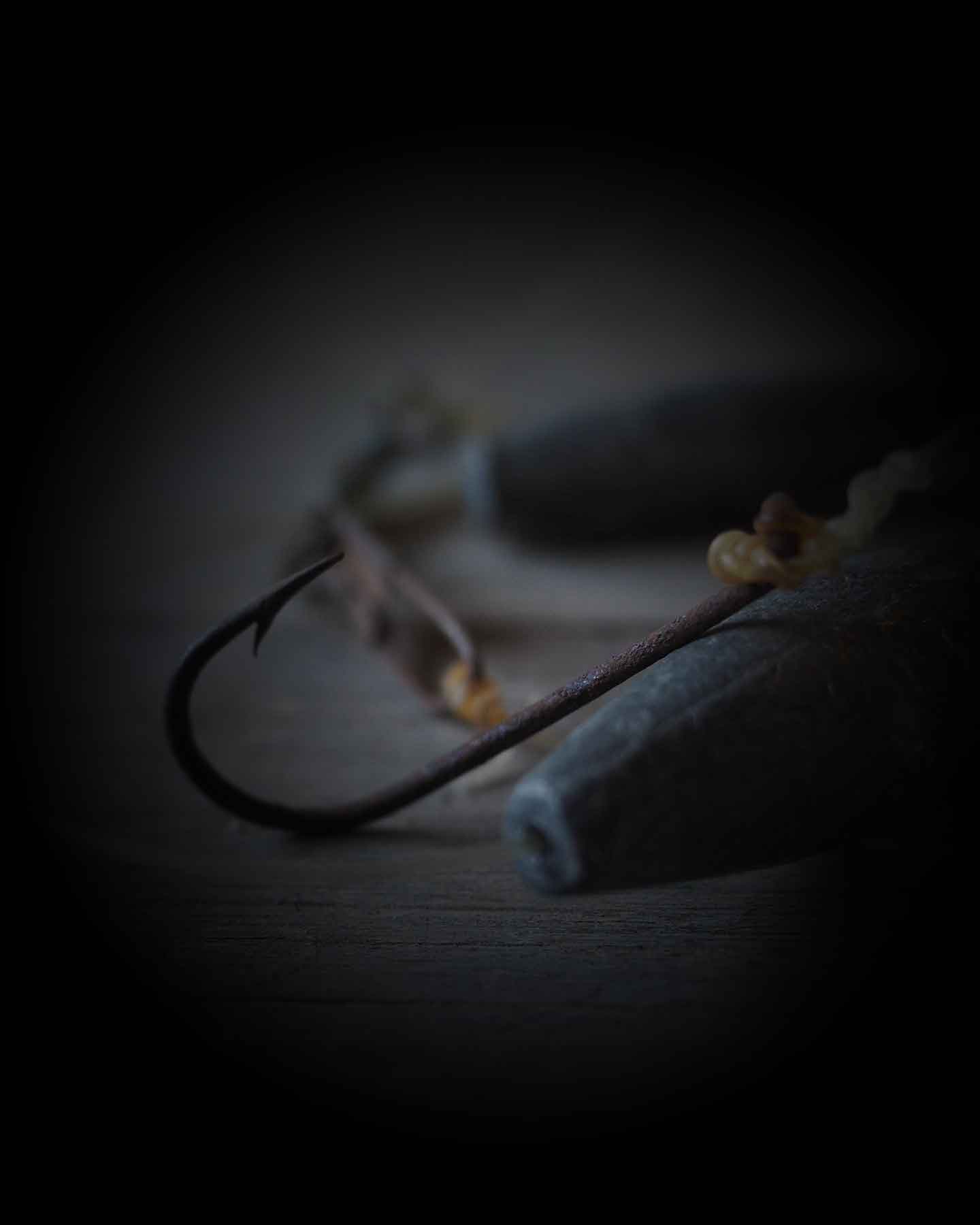

Last of all he would clean and dry his gear. Knives were washed and carefully packed, hooks and lures replaced in old tobacco tins, sinkers in an old coffee tin and lines coiled and fastened to wooden spools. He took special care with the ebony ruler and the gaff. One of his grandfather’s prized possessions was a piece of ebony 18 inches long, a circular leather thong drilled through one end which he would loop around his wrist. It had been given to him by a client who had managed the local bank after the bank had decided that the round ebony rulers used to roll down the pages of the ledgers were old-fashioned and needed to be replaced by flat wooden or aluminium rulers. The old rulers were made of ebony, one of the hardest woods imaginable so that they would never wear out. Banks are like that, they do not like spending money and if they have to, they only like spending it once. The rulers were circular, not flat, so the clerks could roll them down the page, liberating each line in the ledger one at a time in order to be annotated and, occasionally, deleted. His grandfather had, with not inconsiderable effort, drilled a hole in one end of the ebony ruler and tied through a leather thong. Looped around his wrist, it efficiently dispatched even the most unwilling of fish although he reserved it mostly for the larger uncooperative sharks which occasionally disturbed the nets. Almost 90 years later notwithstanding the ravages of salt and sun, the ebony ruler was as hard and unyielding as it ever had been, although the Fisherman had replaced the leather thong several times. That is not to say that it had not always been used to subdue unruly fish. From time to time in his grandfather’s day and later his father’s day it had been deployed to settle territorial misunderstandings regarding fishing territory and netting rights. These misunderstandings usually took place in the predawn hours, out of sight of land and curiously were never reported to the police. “Similarly, his grandfather’s handmade fish gaff had been one of his grandfather’s most loved possessions and, then his father’s. It was in a pocket under the gunwale hanging from two hooks. His grandfather had made it from a hardwood pole six feet long, a cast-iron shark hook and whip cord. Much of the fishing tackle in his grandfather’s day and and even his father’s, had been handmade. Nets were woven from wax cotton rope, floats were hand cut from cork, and sinkers were cast from lead sheets taken from old car batteries. The gaff was a vicious thing, the point of the hook honed on a whetstone by his grandfather, so it was razor-sharp and able to penetrate sandpaper skin of a shark with ease. Painted bright red with red enamel paint it had been used for other things on occasion but not by the Fisherman and to his knowledge not since the notorious salmon netting wars of the late 1940s. Nonetheless, it was a comfort to him to have it tucked under the gunwale in case he ever needed it. Just like his father’s 303 rifle and the Heckler and Koch pistol in the concealed compartment. You just never know when you might need something like that, he would often say to himself.